Introduction Link to heading

As part of the OSS-Fuzz-Gen project, we’ve been working on generating fuzzing harnesses for OSS-Fuzz projects with the goal of improving fuzzing coverage and unearthing more vulnerabilities.

Results previously published from our ongoing work described in our blog post showed promising results, with absolute coverage increases of up to 35% across over 160 OSS-Fuzz projects, and 6 new vulnerabilities discovered. However, this work only applied to projects already integrated into OSS-Fuzz as it uses the existing fuzzing build setups scripts in the given OSS-Fuzz project.

Recently, we experimented with generating fuzzing harnesses for arbitrary C/C++ software projects, using the same LLM techniques.

The primary goal of our efforts are to take as input a GitHub repository and output an OSS-Fuzz project as well as a ClusterFuzzLite project with a meaningful fuzz harness. In this blog post we will describe how we automatically build projects, how we generate fuzzing harnesses using LLMs, how these are evaluated and list a selection of 15 projects that we generated OSS-Fuzz/ClusterFuzzLite integrations for and have upstreamed the results.

Generating OSS-Fuzz integrations with LLM harness synthesis Link to heading

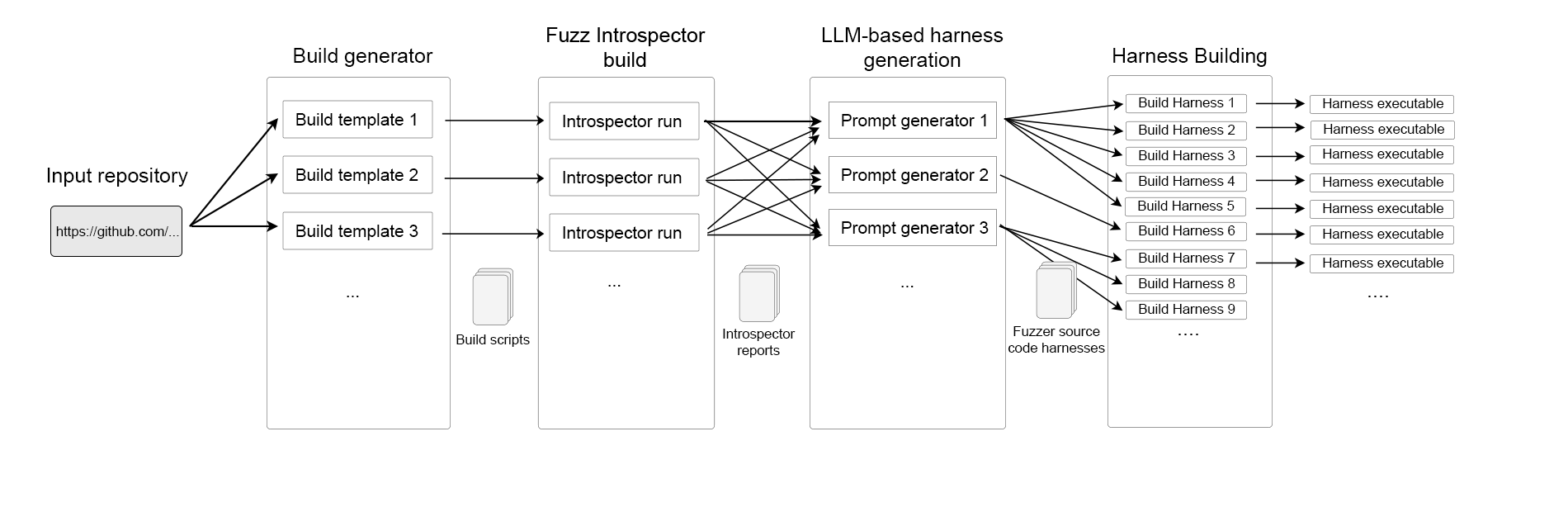

The high-level process for generating fuzzing harnesses from scratch takes as input a URL to a GitHub project and then follows a four step approach:

- Build generator: Try building the project using a set of pre-defined auto-build heuristics and capture the output of the build heuristics. If no build succeeds, do not continue.

- Fuzz Introspector build: For each successful build, rebuild the project under analysis of Fuzz Introspector in order to extract a myriad of program analysis data as output in a Fuzz Introspector report.

- LLM-based harness generation: Synthesize harnesses by way of LLMs where the prompts are based on the program analysis data from Fuzz Introspector report.

- Harness Building: For each generated harness, build it using the build scripts generated from step (1) and run each harness for a number of seconds to evaluate its runtime performance. Log results from runtime for later inspection. For each harness wrap it in an appropriate OSS-Fuzz and ClusterFuzzLite project.

The output of the above is a set of OSS-Fuzz/ClusterFuzzLite projects with LLM-generated harnesses, build scripts, Dockerfiles and output from runtime evaluations. The following figure visualizes the approach, and we will now go into further details with each of the above steps.

Step 1: Auto-build target project Link to heading

The first step intends to build the target project. In the case of C/C++ projects this is a non-trivial problem because, in comparison to several managed languages, there is limited consensus on how to build projects. There are multiple build systems, e.g. Make, CMake, Bazel, Ninja and so on, some projects rely on third-party dependencies to be installed on the system that builds the project, and some projects may rely on multiple commands to create the build artifacts. In addition to this, in order to build the code in a fuzzer-friendly manner we need to ensure certain compiler flags, e.g. to enable sanitizers, and compilers are used for the compilation.

The strategy we have opted for auto-building projects for a fuzzer-friendly build is creating a set of generalized build scripts by abstracting the existing build scripts in OSS-Fuzz. These generalized build scripts are template-like and include, for example, general build approaches based on Make, CMake and also compiling source files directly. We call these generalized build scripts for “build heuristics”. The build heuristics also include features for building the target code statically, since this is a requirement by OSS-Fuzz, and techniques for disabling certain options there may be available in the target projects’ build set up. We added these options because we observed several libraries where default options may not be fuzz-compatible and disabling these would successfully build the target projects.

Upon successful execution of a build template, we search for the binary artifacts created by the build. Specifically, we are interested in the static archives produced by the build since to run on OSS-Fuzz it is preferred to link harnesses statically. We consider each build that produces at least one static archive to be a successful build, and each successful build is used for further processing in the next steps. The output of this step is a bash build script for each successful build template.

To provide intuition for how the build scripts look, consider the following two examples.

Example 1, lorawan-parser build script (PR):

autoreconf -fi

./configure

make

$CC $CFLAGS $LIB_FUZZING_ENGINE $SRC/fuzzer.c -Wl,--whole-archive $SRC/lorawan-parser/lw/.libs/liblorawan.a -Wl,--whole-archive $SRC/lorawan-parser/lib/libloragw$SRC/.libs/libloragw.a -Wl,--whole-archive $SRC/lorawan-parser/lib/.libs/lib.a -Wl,--allow-multiple-definition -I$SRC/lorawan-parser/util/parser -I$SRC/lorawan-parser/lib/libloragw/inc -I$SRC/lorawan-parser/lib -I$SRC/lorawan-parser/lw -o $OUT/fuzzer

Example 2, simpleson build script (PR):

mkdir fuzz-build

cd fuzz-build

cmake -DCMAKE_VERBOSE_MAKEFILE=ON ../

make V=1 || true

$CXX $CXXFLAGS $LIB_FUZZING_ENGINE $SRC/fuzzer.cpp -Wl,--whole-archive $SRC/simpleson/fuzz-build/libsimpleson.a -Wl,--allow-multiple-definition -I$SRC/simpleson/ -o $OUT/fuzzer

Step 2: Extract program analysis data using Fuzz Introspector Link to heading

The next step is to extract data about the program under analysis so that we can use it in a programmatic manner. We need this for two reasons. First, in order to select functions that are good candidates for fuzzing in the target project. Second, we need to be able to programmatically describe the program under analysis in a way that allows us to generate LLM prompts that describe the source code in a human-readable manner.

To achieve this we build the target under analysis, using the build scripts from the previous step, in combination with Fuzz Introspector. Fuzz Introspector is an LLVM-based program analysis tool that extracts a lot of data useful for fuzz introspection and also program analysis in general. For example, for each function in the target project Fuzz Introspector provides data such as function signature, cross-reference information, source code, cyclomatic complexity, call tree and more. This is all useful for our LLM-based harness generation since the goal is to present the LLM with a prompt that gives a precise technical description of the target under analysis.The output of this step is an introspector report for each build script.

The json snippet below is a sample subset of the data that Fuzz Introspector provides for the json_validate function in the lorawan-parser project. The full data is available in this Gist and this type of data is provided to each function in a target codebase. We have stripped the sample for a number of keys in the json output to focus primarily on the data that we use in OSS-Fuzz-gen. Specifically, during OSS-Fuzz-gen harness synthesis we use of the data below:

- Cyclomatic complexity data to highlight functions of interest.

- Callsite to identify sample locations a given function is used.

- Debug information to present to the prompt with program context about the target function.

- Source code location to extract source.

This is a target function that our approach successfully generated an OSS-Fuzz integration for.

{

"Func name": "json_validate",

"Functions filename": "/src/test-fuzz-build-2/./lib/json.c",

"Function call depth": 7,

"Cyclomatic complexity": 4,

"Functions reached": 45,

"Reached by functions": 0,

"Accumulated cyclomatic complexity": 212,

"ArgNames": [

"json"

],

"callsites": {

"skip_space": [

"./lib/json.c#json_validate:437",

"./lib/json.c#json_validate:441"

],

"parse_value": [

"./lib/json.c#json_validate:438"

]

},

"source_line_begin": 434,

"source_line_end": 446,

"function_signature": "bool json_validate(const char *)",

"debug_function_info": {

"name": "json_validate",

"is_public": 0,

"is_private": 0,

"func_signature_elems": {

"return_type": [

"DW_TAG_base_type",

"bool"

],

"params": [

[

"DW_TAG_pointer_type",

"DW_TAG_const_type",

"char"

]

]

},

"source": {

"source_file": "/src/test-fuzz-build-2/lib/json.c",

"source_line": "433"

},

"return_type": "bool",

"args": [

"const char *"

]

}

},

Step 3: LLM-based harness synthesis Link to heading

The next step is to use LLMs to generate fuzzing harnesses. To do this, we have implemented several “harness-generators” that take as input the introspector reports and use this to create human-readable (LLM-readable) prompts which direct the LLM towards creating fuzz harnesses. The high-level idea is to generate textual descriptions of the target functions that are likely to produce a good harness by the LLM. To this end, for each function we consider a likely good candidate for fuzzing we have features for including in the prompts:

- Description of the target function’s signature, with complete types, of the target program

- Description of specifically which header files are available in the target project.

- Examples of cross-references that use the target function to present sample code patterns involving the target function.

- The actual source code of the target function.

- Provide basic guidance to the LLM, such as the need for wrapping it in

LLVMFuzzerTestOneInput.

The output of this step is a set of fuzzing harnesses produced by LLMs. Specifically, we generate Y amounts of harnesses, where Y is the number of functions to target in the program under analysis.

The harnesses that perform the best for each project are in general those that target high-level functions in the target project where the given function accepts fairly raw input data and does not rely on a complex initialization set up. This includes top level functions to, e.g. parse a given string, read a certain file and similar. The interesting parts of the LLM harness synthesi is that the LLM generates the correct initialization logic, provides the correct data types seeded with fuzz data and also provides correct cleaning up logic. To this end, we consider our approach to likely be useful for a lot of open source projects that are by nature fuzzing-friendly targets.

The following GitHub Gist contains three sample prompts generated by the prompt-generation logic, and also the corresponding harness as output by the LLM. These are all prompts that generated successful harnesses in that the harnesses exercised a meaningful portion of code in the target as well as based on human investigation were determined to be good harnesses.

The following examples show fuzzing harnesses generated by our approach.

Example 1, nanosvg harness (PR):

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include "nanosvgrast.h"

#include "nanosvg.h"

#include "stb_image_write.h"

int LLVMFuzzerTestOneInput(const uint8_t *data, size_t size) {

// Ensure null-terminated string

char* data_copy = (char*)malloc(size + 1);

memcpy(data_copy, data, size);

data_copy[size] = '\0';

// Dummy arguments

const char* dummy_filename = "dummy.svg";

float dummy_value = 1.0f;

// Call the target function

NSVGimage* result = nsvgParse(data_copy, dummy_filename, dummy_value);

// Free memory

if (result) {

nsvgDelete(result);

}

free(data_copy);

return 0;

}

Example 2, tinyexpr harness (PR):

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include "minctest.h"

#include "tinyexpr.h"

int LLVMFuzzerTestOneInput(const uint8_t *data, size_t size) {

if (size == 0) {

return 0;

}

char *input = (char*)malloc(size + 1);

if (!input) {

return 0;

}

memcpy(input, data, size);

input[size] = '\0';

te_variable vars[] = {{ "x", 0 }};

int error;

te_expr *result = te_compile(input, vars, 1, &error);

free(input);

te_free(result);

return 0;

}

Example 3, Simpleson harness (PR)

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include "json.h"

extern "C" int LLVMFuzzerTestOneInput(const uint8_t *data, size_t size) {

if (size == 0) {

return 0;

}

// Copy input data to a null-terminated string

char* input = new char[size + 1];

memcpy(input, data, size);

input[size] = '\0';

try {

json::jobject::parse(input);

} catch (...) {

// Catch all exceptions thrown by the target code

}

delete[] input;

return 0;

}

Step 4: Build and run each generated project Link to heading

The final step is to verify that the build scripts combined with the fuzzing harnesses can build actual executables, and for each successfully built executable to verify that the harness is meaningful. Specifically, from step (1) we have a set of build scripts that successfully build the project under analysis and from step (3) we have a set of harnesses, for each successful build script, that targets the project under analysis. We now combine these by running the build script and creating a command for building a given harness against the output static libraries.

For each successfully built harness we run the given harness for a set period of time (40 seconds) in order to collect runtime logs, and for each successfully built harness we wrap the relevant artifacts in an OSS-Fuzz project as well as CluserFuzzLite project that can be run directly using the OSS-Fuzz infrastructure. The logs from runtime are then used for later inspection to determine if a harness was good, using factors such as edge coverage and how long the harness ran without running into any issues. At this stage, this is then verified by a human to determine if the integration is considered to the standard of an OSS-Fuzz/ClusterFuzzLite integration.

Results Link to heading

The goal of our efforts is to enable continuous fuzzing for arbitrary open source projects. We ran our approach on a benchmark of C/C++ projects and have captured a subset of the successful integrations in order to integrate them to OSS-Fuzz or upstream ClusterFuzzLite.

During the initial runs of the fuzz harnesses three memory corruption issues were reported and also a couple of memory leakages. We manually debugged the issues to create fixes and report the issues upstream. The memory corruption issues were all heap-based read buffer overflows, where the heap-aspect comes from the harnesses allocating data on the heap. An interesting aspect for one of the discovered issues is that the project already had CodeQL running as part of its continuous integration workflow, however, CodeQL did not find the issue as reported by the automatically generated fuzzing set up.

In addition to the issues reported we also collected code coverage for the projects based on the coverage achieved from a 40 second run. The below table contains references to the 15 projects that we upstream for continuous fuzzing. These project integrations were all fully automatically generated, with the caveat that for some of the pull requests we made follow-up commits that only addressed cosmetic changes, such as beautifying the code and making the build scripts more lean.

| Target GitHub repository | Integration PR | Code coverage | Issues found and fixed |

|---|---|---|---|

| https://github.com/memononen/nanosvg | PR | 41% | |

| https://github.com/skeeto/pdjson | PR | 78% | |

| https://github.com/gregjesl/simpleson | PR | 35% | PR |

| https://github.com/kgabis/parson | PR | 42% | |

| https://github.com/rafagafe/tiny-json | PR | 85% | |

| https://github.com/kosma/minmea | PR | 37% | |

| https://github.com/marcobambini/sqlite-createtable-parser | PR | 14% | PR |

| https://github.com/benoitc/http-parser | PR | 1.5% | PR |

| https://github.com/orangeduck/mpc | PR | 49% | |

| https://github.com/JiapengLi/lorawan-parser | PR | 11% | |

| https://github.com/argtable/argtable3 | PR | 0.8% | |

| https://github.com/h2o/picohttpparser | PR | 41% | |

| https://github.com/ndevilla/iniparser | PR | 46% | |

| https://github.com/codeplea/tinyexpr | PR | 34% | |

| https://github.com/vincenthz/libjson | PR | 10% |

Continuing the LLM harness synthesis loop Link to heading

The LLM-based synthesis generation does not stop once a target project has integrated into OSS-Fuzz. In fact, at this point, the existing capabilities of OSS-Fuzz-gen will come into play and continuously, on a weekly basis, experiment with new harnesses for the target project that takes into account the project’s current coverage status on OSS-Fuzz. In particular, OSS-Fuzz-gen will analyze which are the most promising new targets for a given OSS-Fuzz project and use our extensive LLM-based harness synthesis to evaluate, test and run new harnesses for a given project. To this end, the synthesis will continue and improve as a given project is continuously fuzzed.

The overall goal we’re working towards is to provide a fully automated solution to improve the security of projects with fuzzing, from the initial build integration, continuous fuzz harness generation, bug reporting and triage, and automatic patching.

Contribute to the efforts Link to heading

The efforts described in this blog post are open sourced in OSS-Fuzz-gen. We invite contributions, and would like to highlight specific efforts that will have a positive impact on our OSS-Fuzz from scratch generation:

- Adding new build heuristics to enable compilation and fuzz introspector analysis of new projects. The key here is that any improvements in this context will open up analysis of new open source projects, and will ultimately be a positive sum outcome.

- Adding additional prompt generators with a given example of success. The approach described in this blog runs each prompt generator without affecting the other prompt generation approaches, and because of this there is no need to worry of causing regressions in our existing prompt generators. As such, contributions are welcome for any new prompt generation approach that successfully creates harnesses for a project where the existing prompt generation approaches come short. We encourage the use of program analysis data from Fuzz Introspector in order to provide source code context.